A recent report in The New York Times highlight the poor states and failures of hospitals in Uganda. They write about pregnant women arriving at hospitals in time to deliver, but when complications arise, no one is there to help them. The tragic events at Arua Hospital is unfortunately not a unique event.

Such failures are unfortunately not seldom. The New York Times article point to the lack of priority given by the Ugandan Ministry of Health. In my view it also points to a failure over many years by the international donor communities.

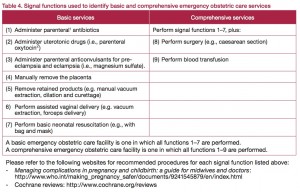

Where as much emphasis has been given to HIV work, and immunisations, donors and NGOs have been reluctant to support and strengthen institutions. Hospitals are essential to reduce maternal deaths. Most deaths would be averted if the pregnant women would deliver at hospitals near to their homes, and such a hospital need to have trained staff to do Comprehensive emergency obstetric care (see figure for more information).

Many NGOs and donor government unfortunately believe that providing antenatal coverage is enough to reduce maternal deaths. Unfortunately, such logic is only true to a certain extent. Good antenatal services will reduce maternal deaths if it works jointly with hospitals. Antenatal work in the communities and at peripheral health posts must in time refer women in need of comprehensive emergency obstetric care. Experience from many countries show that antenatal care as stand-alone work will not reduce maternal deaths.

In our project in Ethiopia we try to improve the quality of hospitals, and support the Ministry of Health to upgrade health centres to small hospitals so pregnant women can get use essential services near to their homes. The aim is there should be one well-functioning institution providing comprehensive emergency obstetric care for every 150.000 people.