Deaths from maternal causes represent the leading cause of deaths among women of reproductive age in Ethiopia. Thus, in line with the Millennium Development Goal for maternal health (MDG-5), this health project aims to reduce maternal mortality among the target population by two-thirds by 2015.

Experience from other countries show that two conditions are needed to reduce maternal deaths: Staff should be able to carry out comprehensive emergency obstetric care, and these services should be available to and used by pregnant women.

Vision and aims of project

In this public programme, we work with the Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples’ Regional State (SNNPRS) Health Bureau of Ethiopia (RHB) to improve maternal health and reduce maternal and neonatal deaths among the target population. The target population for this project are pregnant women in the following administrative areas of south-west Ethiopia: Gamu Gofa Zone, South Omo Zone, Basketo Special Woreda, Dirashe Special Woreda and Konso Special Woreda.

The Project works with two levels of health institutions responsible for delivery services. Health extension workers are responsible for the kebele antenatal work, and hospitals and health centres are responsible for delivery services in the woredas and zones.

Our work has four components:

- Train non-clinician physicians (health officers) and midwives to carry out comprehensive emergency obstetric care (see

- Equip institutions to carry out comprehensive obstetric services

- Make delivery services available through health extension workers to all local communities and thus to pregnant women among a population of 2.6 million people.

- Using a simple, cost-effective, and sustainable tool to monitor maternal and newborn deaths. These community-based birth and death registries use health extension workers to register all births and deaths that occur in rural communities

Work in 2009

During 2009, 10 health officers, 10 anaesthetic nurses and 10 scrub nurses received training in Arba Minch Hospital. They now work at their home institutions. It is encouraging to see the these teams of health staff at Kemba and Konso Health centres, and Chencha, Saula, Gidole and Arba Minch hospitals routinely do emergency obstetrics, including caesarean sections. In November another four health officers and anaesthesia nurses started their training. In addition, we have trained about 150 HEWs and 30 midwives and clinical nurses.

Our project represents the first try In Ethiopia to train non-clinician physicians on a larger scale, and we are encouraged to see that comprehensive obstetric care is done at health centres in Konso and Kemba. In 2009, the number of caesarean sections increased by almost fifty per cent among our target populations, and the number of institutions routinely doing emergency obstetric care increased from two to seven.

Monitoring of work

As in many other African countries, Ethiopia lacks information on how many mothers die before, during or after delivery. Thus, by involving staff from regional health authorities, universities and health colleges, we have developed tools for community based birth registries. In 2009 we carried out pilot studies, and validated the tools to register births and deaths. In December we started birth and death registration for the population in Dirashe Special Woreda. This registration will enable the project to oversee if maternal deaths are reduced by two-thirds by 2015. Two master students now study at Gondar University, and one PhD student shall soon start at the University of Bergen.

We use experienced staff to follow and support the health officers at the rural institutions. In addition we continuously review the quality of the work at all institutions. So far, the results are encouraging and are comparable similar work started in other African countries.

Priorities for 2010

In 2010 we shall continue to strengthen the institutions, and through our Quality assurance, we systematic monitor and evaluate the work to ensure that standards of quality are being met. In 2010, our main emphasis shall be to strengthen the capacity of health extension workers, health posts and smaller health centres. The goal is to improve institutional birth coverage and that pregnant women in need of institutional care are referred in time.

More information is found at:

http://www.lindtjorn.no/page1/page11/page11.html

http://bernt.w.uib.no/my-research-areas/reproductive-healthproject/reducing-maternal-and-neonatal-mortality/

http://bernt.w.uib.no/training-programme/

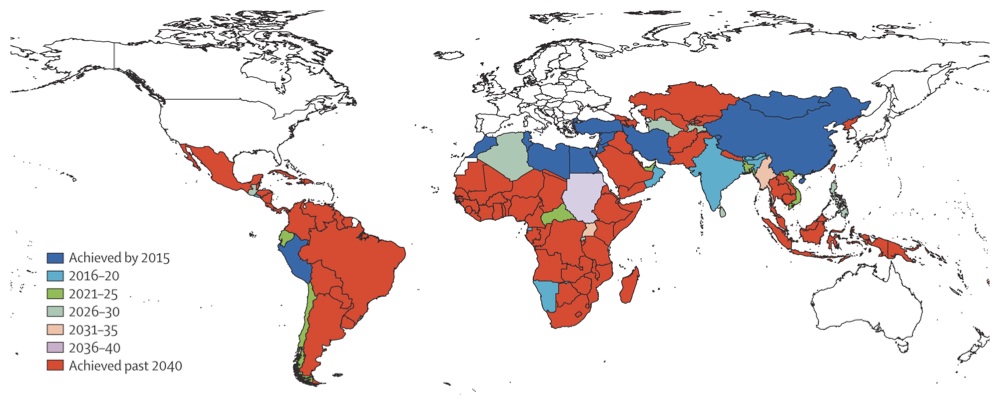

A recent article in The Lancet says only nine of 137 developing countries will achieve targets to improve the health of women and children. Although progress is speeding up in most countries, and especially to reduce child deaths, efforts to cut deaths among pregnant women and new mothers by three-quarters will not be achieved before 2040 in most sub-Saharan African Countries (see map copied from The Lancet article).

A recent article in The Lancet says only nine of 137 developing countries will achieve targets to improve the health of women and children. Although progress is speeding up in most countries, and especially to reduce child deaths, efforts to cut deaths among pregnant women and new mothers by three-quarters will not be achieved before 2040 in most sub-Saharan African Countries (see map copied from The Lancet article).

There are unfortunately many hospitals in Ethiopia and in Africa that do not work as expected. They lack staff, or equipment. Often they lack staff doing essential interventions such as caesarean sections.

There are unfortunately many hospitals in Ethiopia and in Africa that do not work as expected. They lack staff, or equipment. Often they lack staff doing essential interventions such as caesarean sections.