![]() In global health, operational research is an idea increasingly used by donors and policy makers. It involves analytical methods to help improve public health interventions and treatment of diseases in real-life situations. It is thus different from randomized clinical trials that determines efficacy of an intervention in a strictly controlled environment with inclusion and exclusion criteria, whereas operational research assess effectiveness within routine, and real-life settings.

In global health, operational research is an idea increasingly used by donors and policy makers. It involves analytical methods to help improve public health interventions and treatment of diseases in real-life situations. It is thus different from randomized clinical trials that determines efficacy of an intervention in a strictly controlled environment with inclusion and exclusion criteria, whereas operational research assess effectiveness within routine, and real-life settings.

Recently Zachariah and colleagues (2009) defined operational research as: “The search for knowledge on interventions, strategies, or tools that can improve the quality, effectiveness, or coverage of programmes in which the research is being done”.

Operational research involves descriptive, case–control, and cohort analysis. Some say that basic science research and randomised controlled trials is not operational research. However, effectiveness trials refer to whether an intervention works in people to whom it has been offered, and should in my view form an integral part of operational research. Results from such randomized trials can be are translated to benefit in the diverse setting of routine care.

For a health programme, the relevance of such research is whether it contributes to an improved performance or influences policy change at district, national, or even international levels.

Some examples of operational research from south Ethiopia include:

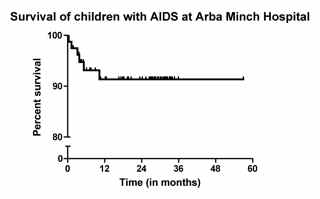

- Antiretroviral treatment in resource limited settings (Jerene et al 2006): This cohort study assessed feasibility and effectiveness of antiretroviral therapy by use of historical controls.

- An effectiveness trial in south Ethiopia aimed to evaluate if community health workers could improved smear-positive case detection and treatment success rates (Datiko and Lindtjørn, 2009). The study showed that involving of health extension workers (HEWs) in sputum collection and treatment improved smear-positive case detection and treatment success rate, possibly because of an improved service access. This finding has policy implications and could be applied in settings with low health service coverage and a shortage of health workers.

References:

Zachariah R, Harries AD, Ishikawa N, Rieder HL, Bissell K, Laserson K, Massaquoi M, Van Herp M, & Reid T (2009). Operational research in low-income countries: what, why, and how? The Lancet infectious diseases, 9 (11), 711-7 PMID: 19850229

Jerene D, Naess A, & Lindtjørn B (2006). Antiretroviral therapy at a district hospital in Ethiopia prevents death and tuberculosis in a cohort of HIV patients. AIDS research and therapy, 3 PMID: 16600050

Datiko, D., & Lindtjørn, B. (2010). Cost and Cost-Effectiveness of Treating Smear-Positive Tuberculosis by Health Extension Workers in Ethiopia: An Ancillary Cost-Effectiveness Analysis of Community Randomized Trial PLoS ONE, 5 (2) DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009158

There are unfortunately many hospitals in Ethiopia and in Africa that do not work as expected. They lack staff, or equipment. Often they lack staff doing essential interventions such as caesarean sections.

There are unfortunately many hospitals in Ethiopia and in Africa that do not work as expected. They lack staff, or equipment. Often they lack staff doing essential interventions such as caesarean sections.